One of the countless priceless takeaways for me from my MFA program at Antioch University in L.A. was the practice of maintaining a commonplace book. This gift of an idea, as I recall, was given to our graduating class by one of the commencement speakers on our last day together, June 24, 2007: Keep a commonplace book from this point onward, he advised. Use it to write about each book that you read. Preserve what you learn from those books. They are your teachers….

Most of what commencement speakers say to graduating students gets lost in the nervous excitement of these momentous occasions, but his suggestion stuck with me. I don’t remember his name (although I can still see him: large, formidable, middle-aged, dark-haired); but I do remember that as he spoke I envisioned an album in which thoughts, inspirations, characters, plots, scenes, dialogue – like so many colorful exotic butterflies — plucked from books, would be pinned for all time.

That commencement speaker told us that commonplace books — which I’d never before heard of — have a long and rich literary history. Neither diaries nor journals, which are generally chronological and introspective, commonplace books have been used for hundreds of years by readers, writers, students, and scholars as an aid for remembering useful concepts or facts they have learned.

“Commonplace” in this sense, I later learned, is a translation of the Latin term locus communis, which means “a theme or argument of general application,” such as a statement of proverbial wisdom. In this original sense, commonplace books were collections of such sayings. Scholars have expanded this to include any manuscript that collects material along a common theme by an individual.

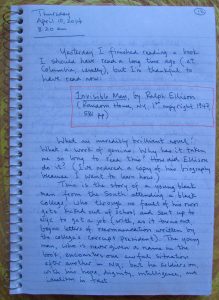

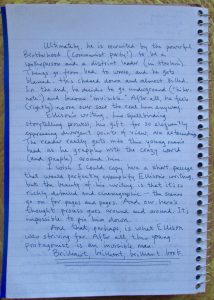

So, ever since my graduation from AULA ten years ago, I’ve followed that speaker’s advice and kept a commonplace book by my bedside table, in which I write up the books I read. Not really book reports or book reviews, these one- or two-page entries for me are more like responses: The book has spoken to me in many ways, and I claim the right to talk back. They’re also a way to chronicle the books I’ve read. Otherwise I fear I might forget.

Here is my volume two:

Leafing through it I’m reminded of one of the main reasons I read books: to be an armchair traveler, to other places and other times. (As Emily Dickinson so aptly put it: “There is no frigate like a book to take us lands away…. How frugal is the chariot that bears the human soul.”)

The books written up in this volume have taken me to such locales as post-WWII Southern Rhodesia (Doris Lessing), South Africa during the Apartheid era (Trevor Noah), early 20th century Mexico (Carlos Fuentes), post-WWI Australia (M.L. Stedman), France during the German occupation (Anthony Doerr), 21st century East Africa (Jeffrey Gettleman), war-torn Chechnya (Anthony Marra), post-colonial Uganda (Dinaw Mengestu), 17th century Delft, Holland (Tracy Chevalier), as well as Toronto, Canada (Margaret Atwood).

I’ve read books by famous older women authors whom I’ve had the honor of interviewing for my WOW blog (Sallie Bingham and Joyce Appleby, for example), and books about famous male authors whom I’ve fallen in love with through their own books (Ralph Ellison, for one).

I read four terrific books about San Miguel de Allende before deciding to retire here – the best one being Carol Merchasin’s This is Mexico. And the list goes on, embracing my favorite subjects, whether told as fiction or nonfiction, such as history, exploration, and invention.

The book I’m reading now, however, is a whole different story. It’s the semi-satirical political novel by the Nobel-winning American author Sinclair Lewis, It Can’t Happen Here, published in 1935. I’m afraid it’ll be a while before I write this book up in my commonplace book because I’m reading it so slowly, only one or two chapters a night. It’s a painful read for me – too close to the current reality — but I’m determined to see it to its end.

In brief: the novel describes the rise of a cunning, manipulative conman named Berzelius Windrip, who is elected President of the United States on a populist platform, promising to restore the country to prosperity and greatness. After his election, Windrip takes complete control of the government and imposes an authoritarian rule (similar to Hitler’s). The novel’s plot centers on newspaper editor Doremus Jessup’s opposition to the new regime and his subsequent struggle against it as part of a liberal rebellion.

Lewis’s prescience is chilling. It’s no wonder that after the 2016 election of Donald Trump, sales of It Can’t Happen Here surged, and it became a best seller earlier this year.

There is another, more commonly used definition of the word “commonplace,” of course. It is “ordinary.” What we all can agree on, I think, is that we are not living in “ordinary” times. As I read Lewis’s terrifying book, written eighty-two years ago, I ask myself, Can it happen here? Or, rather, Is it already happening here? I trust by the time I respond to this novel in my commonplace book, the story – both the fictional and the real-life version — will have a more hopeful ending.