The coup that occurred in Gabon this week was a yawn to most news consumers in the West. Just another disputed election and military takeover in another African country; there have been many in recent years. So what.

At the time I read about this coup in the New York Times early Wednesday morning, it had drawn only ONE comment, whereas normally by this time lead NYTimes articles garner comments in the hundreds, sometimes thousands. Who cares about Africa after all? And Gabon? Where’s Gabon?

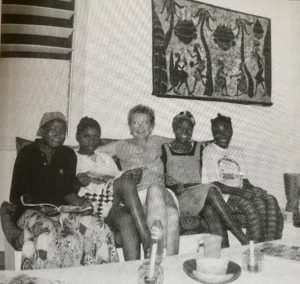

Well, I, for one, care, as do most of my fellow Peace Corps volunteers who served there decades ago, when such doors were still open to us. I was (informally) adopted by a Gabonese family in Libreville, the capital, in 1996, when I was in Peace Corps training there, and I’ve stayed in touch ever since with one special member of the family, Yolande, who calls herself my Chocolate Sister, and I, her Vanilla Sister.

I wrote to her immediately to ask how things were, and she reassured me that “all is well in Gabon.” She added, “The coup came as a help from God to avoid the much anticipated bloodshed and civil war following the announcement of the presidential election results on August 30.” She said we should all pray that “peace, happiness and prosperity be the daily bread of all the Gabonese people,” and she sent me her family’s love “in abundance” before closing with, “Your Chocolate Sister.”

I was a health and nutrition volunteer for two years in a town called Lastoursville, a stop on the country’s one train line, in the rain-forested interior of this oil-rich, timber-rich, mineral-rich little country, where most of the people outside of the capital live in dire poverty. The then-president, Omar Bongo, was said to be one of the richest men in the world. At his death in 2009, his son, Ali, took over as president. This dynasty has lasted over half a century. It now appears, as a result of this coup, to be nearing its end.

I wrote about my two-year experience in Gabon in my memoir-with-recipes, HOW TO COOK A CROCODILE (Peace Corps Writers, 2010). Here is an excerpt, which I think is relevant, from one of its chapters, “Friday Night Brights,” to give you a sense, perhaps, of being there and maybe even caring about the outcome of this military coup:

“Beef or chicken, sir?” I ask each boy in turn, pretending I’m a flight attendant, going down an aircraft’s aisle, taking dinner orders on a pad. It’s Friday night, and my six o’clock English class, held in my living room and free to any high school student who cares to attend has just begun.

I try to make these classes fun for them. Instead of teaching English grammar from a dry text – something they surely get enough of in their English classroom at Lastoursville’s regional lycee (high school) – I try to instigate lively discussions and enact real-life situations, all in English only.

A core group of about five earnest teenage boys – always clean and well dressed, in long-sleeved white shirts and pressed black trousers – attend these Friday night classes fairly faithfully. Other boys drop in from time to time, perhaps out of curiosity.

Occasionally, a few teenage girls come, too; but they are mostly quiet, sitting close together on my sofa, giggling among themselves nervously. The girls’ attention is focused solely on the boys; they show no interest in learning to speak English or are too shy in the presence of the boys to try.

The boys who attend regularly, however, are bright, bold, and ambitious. They have goals and dreams – especially of getting out of Gabon one day and making something of themselves in the world. They realize that the ability to speak English well, as well as their second language, French, would benefit their careers. So they take advantage of this free opportunity and apply themselves. They are also particularly good-natured about going along with whatever unconventional ideas I dreamed up for making the class fun.

On this night we’re pretending they are all scholarship recipients to universities in the United States, and we’re on a flight from Libreville to New York, where they’ll be making connections to their respective beneficent universities. This pretense pleases them. From their broad smiles and widening eyes, I can see that it’s fueling their fantasies. Scholarship? University? United States? These powerful English words speak to them. They need no translation.

…

On another evening, though, I made a big mistake. I raised the verboten topic of politics, hoping it might lead to a lively conversation. We were sitting in a circle in my living room, four of the core boys and myself, when I too straightforwardly shared my unvarnished view that the Gabonese people seemed to me to be too apathetic about their situation. Why did they allow their government to do whatever it wished? Why didn’t they stand up for themselves and demand their rights?

“Apathy is complicity,” I said, tossing out these weighty English words in the hope that the boys would catch their significance and a heated discussion would ensue.

My words fell heavily, and the boys stiffened. Their eyes darted across the length of the louvered windows in my living room. Thierry shook his head slowly from side to side. Regis fixed his gaze on me and drew his right index finger gingerly across his throat. Martial froze. The boys’ body language told me instantly: You mustn’t say these things. People could be watching, listening. We cannot speak ill of President Bongo if we want to live.

Jacques, an active member of the local Christian Alliance church, spoke up. “Papa Bongo takes good care of us,” he said in French. “We live in peace. He is a good president. God put him in office. It is not for us to question God’s plan.” The other boys nodded.

“Ah, yes, of course, you’re right,” I said carefully and slowly in English, then repeated again in French for whoever might have been lurking outside. I didn’t want to put these boys in danger. Free speech was not an option for them, in any language.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

To learn more about Gabon and this recent coup, visit:

- The New York Times: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/30/world/africa/gabon-coup-election.html

- Democracy Now:

- The BBC:

To learn more about HOW TO COOK A CROCODILE or to order a copy, go to my website’s Home page: www.bonnieleeblack.com .