For my Spanish homework this week my maestra, Edith, asked that I write a true story – in Spanish, of course – about a strange (extraño) incident I’d experienced.

Piece of cake, I thought. In a life that has spanned seventy-four years and countless miles so far, I felt I have a lot of material to draw from. But the strangest stories of all for me have come from my eight-or-so years lived on the ground in Africa.

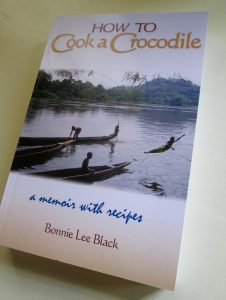

One incident in particular stands out. I gave it only two paragraphs in my Peace Corps memoir, How to Cook a Crocodile, but in my memory it’s as vivid as a full-length feature film.

I was taking the ten-hour train ride — on the country’s one and only train — from Lastoursville, my Peace Corps post in the thickly rainforested interior of Gabon, to the capital city Libreville on the Atlantic coast, to attend a Peace Corps conference.

On the train I happened to sit next to a large, barefooted middle-age Gabonese woman in traditional African dress and head wrap who was using a cellular phone to call her travel agent in Libreville about a flight to Rome.

The first strange thing about this scene was that I’d never before seen anyone use a cell phone in Gabon. This was more than twenty years ago in a country where most barefooted people couldn’t even afford decent food, much less a cell phone. And call their travel agent? About a flight to Rome?

As a Peace Corps volunteer then, I certainly didn’t have a cell phone. Or any other kind of phone, for that matter. In emergencies I used the one pay phone in my town — which was loosely attached to the exterior of the town’s tumbledown post office — on the rare occasions when that phone was working.

When my seatmate finished her call, she turned to me to chat in fast, Gabonese French. Smiling warmly, she explained that she was heading to Rome to see an exorcist affiliated with the Vatican in order to heal one of her eight children, who had been possessed by evil spirits ever since she was eight years old. The girl (the African mother pointed to her daughter sitting behind us) was now twenty-two.

I looked over at the young woman, who seemed to be placidly enjoying the view from the fast-moving train’s window – a jungly blur of greens and browns. I didn’t sense any evil spirits in her. Did she know where she was headed? And why? Who was the crazy one here?

Then the mother did the strangest thing of all. She took an unopened bottle of orange Fanta soda from her bag and proceeded to remove the cap on it with her teeth. Perhaps there are people all over the world, I thought in that moment, whose teeth are strong enough to accomplish this feat, but I’d never seen it done.

I tried to hide my amazement.

She took a big swig straight from the bottle and offered the bottle to me. I politely declined.

“C’est triste,” she said, and I agreed it was sad, that her daughter was so ill. And then we talked about other things.

She told me she was forty-six, and she asked me my age.

“Cinquante et un,” I said. She looked me up and down and nodded approvingly.

“You look really good for fifty-one,” she said. In Gabon at that time few people lived much beyond fifty.

I could go on, but you get the idea. Language is a bridge that spans the whole spectrum, from beautiful to bizarre experiences. If that unforgettable Gabonese mother and I had not had a shared language, we would never have connected. I would have never learned her story. She would not still be living in my mind.

In the two-plus years I lived in Gabon, I managed to learn how to communicate in Gabonese French. Here and now in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, after more than three-and-a-half years, I’m still struggling to grasp Mexican Spanish.

But I refuse to give up! With the help of Google Translate (don’t tell Edith), I’ve just done my Spanish homework. I translated the two short paragraphs about this incident from my Peace Corps memoir. I’m hoping Edith finds my story suficientemente extraño.