“There is no frigate like a book to take us lands away,” Emily Dickinson says in one of my favorite of her poems. Last year several of the books that “took me lands away” were written by Pearl S. Buck.

It hadn’t been since high school in New Jersey in the ‘60s, when we all had to read her Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Good Earth that Pearl Buck had taken me to Asia — a part of the world I’ve never actually visited and will likely never see. Don’t ask me why, but last year I wanted her books to take me there, vicariously, again.

But the three Buck novels I read in the past six months – The Mother, The Hidden Flower, and Imperial Woman – did more than take me to a geographic place far away. They resonated deeply within me as a mature woman.

Her female protagonists are competent, resilient, self-sufficient, and passionate risk-takers. They shatter stereotypes. They break molds. After reading these three, I was hungry to learn more about their creator. Just who was Pearl S. Buck? Why was she speaking so loudly to me now? And why has she seemingly sunken into obscurity?

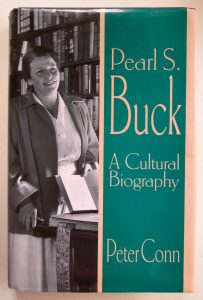

So I sought out a biography of her life and chose now-retired Penn Professor Peter Conn’s meticulously crafted Pearl S. Buck: A Cultural Biography (Cambridge University Press, 1996), which was listed among the best books of 1996 by both Publishers Weekly and Library Journal.

In his narrative Conn reconstructs Buck’s long life and significance and strives to restore this remarkable woman to visibility. He offers a two-pronged portrait: of Buck, a figure greater than history cares to remember, and of the era she helped to shape.

Although perhaps best known as the author of The Good Earth — which became one of the best-selling books of the twentieth century — and as a winner of both the Pulitzer (in 1932) and the Nobel Prize for literature (in 1938), Buck’s career extended far beyond her more than seventy full-length works of fiction and nonfiction (many of which became best-sellers) and well into the public sphere.

Years before most white intellectuals paid much attention to such issues, Conn says, Pearl Buck was passionately committed to the cause of social justice and tirelessly active in the American civil rights and women’s rights movements. She also founded the first international adoption agency.

Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker was born in 1892 to American Presbyterian missionaries to China. She lived the first half of her eighty-year-long life in China and was bilingual from childhood.

According to Conn, “As an adult she would reject the religion in which she was raised.” She rejected her father’s rigid religious beliefs, but she inherited “his evangelical zeal, his sense of rectitude, his passion for learning. She became, in effect, a secular missionary, bringing the gospels of civil rights and cross-cultural understanding to people on two continents.”

Her first marriage, in 1917, to John Lossing Buck, an agricultural economist working in China, lasted seventeen (unhappy) years and produced one child, Carol, who was severely and permanently mentally impaired and ultimately institutionalized in the U.S., which caused Buck lifelong private heartache. As Conn states it, “It goes only a little too far to say that Pearl Buck’s entire career as a writer was anchored in her anxiety for her [only birth] child.”

Buck’s second marriage, in 1935, to Richard Walsh, the president of the John Day Company, became a happy and prosperous thirty-year partnership. Walsh’s publishing company, John Day, was the first to publish Buck’s books, and they would publish everything that Buck wrote from that point on. One commentator called it, “The most successful writing and publishing partnership in the history of American letters.”

Over time Buck and Walsh also adopted seven mixed-race children and divided their time between an apartment in New York City and a sprawling old refurbished farmhouse in Bucks County, Pennsylvania.

Wherever she was, though, she reserved her mornings for writing. “This,” says Conn, “was a habit she had developed in China and would continue to the end of her life.” She wrote 2,500 words per day, covering eight-to-twelve handwritten pages. Between her writing, reading, and correspondence, she sometimes worked fourteen-to-sixteen hours a day.

Pearl Buck became wealthy and famous. Among her close friends were such notables as Eleanor Roosevelt and Margaret Sanger.

She even attracted the hostile curiosity of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who initiated a file on her in 1937, which ultimately reached nearly three hundred pages. Conn writes, “Hoover was afraid of writers because they were America’s least conformable citizens. They made a living by thinking for themselves and saying what they thought.”

Pearl Buck’s life and writing, says Peter Conn, “helped to redefine the idea of a woman’s place in modern society. She was a major public figure, independent and often pugnacious […] Beginning in poverty, she earned millions of dollars and spent lavishly on herself, her family, her friends, and her causes. She lobbied successfully to change American attitudes and policies in the areas of immigration, adoption, minority rights, and mental health.”

But, Conn adds, “I have not written a saint’s life. Pearl Buck, as I have gotten to know her, was a troubled, conflicted, often limited woman, capable of cruelty as well as kindness.”

In other words, she was human.

As I read Conn’s brilliant biography, I couldn’t help but think: What would Pearl Buck say about the issues, especially women’s rights and civil rights, she so vehemently fought for, if she were alive today? I imagine the middle-age Pearl would say something encouraging and hopeful (if terse), such as, “Well, we’re making progress.” The older Pearl, however, the one my age – in her mid-70s – I’m sure would wave a heavy hand and scoff, “No, we haven’t come far enough! We have so much farther to go!”