My Mexican friend Ramiro, who is the most warm-hearted, outgoing, people-loving person I’ve ever known, checks in with me weekly to see how I’m doing. Extrovert that he is, it’s inconceivable to him that anyone could live alone and like it, as I do.

“Aren’t you ever lonely?” he sometimes gently asks.

“Never lonely and never bored,” I tell him. “I always find plenty to do.” I try to explain to him that I love reading books as much as he loves socializing with people. As an introvert-homebody, I have no trouble at all being alone at home. This is a very foreign concept to him. For me, it’s a great advantage during these shelter-in-place times.

Thinking about Ramiro has made me think about how well social distancing might work here in Mexico. In my experience and observation, for most Mexican people physical proximity and social nearness are not second nature, they’re first. Mexicans appear to love gathering in large, happy groups, the closer the better. Among friends, bear hugs and cheek kisses abound. Couples of all ages walk hand in hand and sneak smooches everywhere. Little ones are held and cuddled by the whole family. Realistically speaking, it seems to me, asking a Mexican to practice social distancing is like asking a fish to climb a mountain.

Ramiro tells me that his business — he chauffeurs tourists to and from the airport and takes people on tours of Guanajuato — is flat, because tourism in Mexico has so sharply declined. But he says he’s not worried. Worry doesn’t seem to be in his toolbox. I tell him I could teach him how to do it – because worry is one of the few things I excel at – but he just laughs. “Things will get better,” he says, ever the optimist.

I theorize that Mexicans, steeped in their ancient, proud culture, which has weathered so much, tend to take the long view when it comes to possibly catastrophic events, such as this coronavirus pandemic: It will end. We’ll get through it. Or we won’t. God only knows. Mexicans don’t seem to own panic buttons.

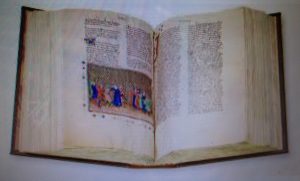

If Ramiro were a book-reading kind of guy – which he isn’t – I would press on him a book I’m reading, or I should say, re-reading, now. I first read this classic in college (a hundred years ago); and, given current events, I’ve recently remembered its gist. Written by Italian author Giovanni Boccaccio in the middle of the 14th century, The Decameron (decameron meaning ten days) follows ten young people – seven women and three men – who escape the city of Florence, Italy, during the Black Death (Bubonic Plague – considered the deadliest plague in human history) raging in Florence in 1348.

The eldest, boldest, leader of the group, twenty-eight-year-old Pampinea, stands up and says to the rest, “What do we here? What wait we for? What dream we of?” and they all agree with her to leave immediately.

They travel a few miles out of the city to stay at a safe, secluded villa in the countryside. There, they decide among themselves to tell stories to each other to pass the time and lift their spirts, which had been so depressed by the plague. Every day for ten days each of the ten young people tells a story – bawdy stories, love stories, funny stories, gender-bending stories, and more – so that after ten days there are one hundred timeless tales about the human condition.

As one Boccaccio scholar put it, “In demonstrating how the moral climate of the city had been altered due to the dehumanizing effects of the plague, Boccaccio allows the narrators, and indeed himself as the author, the freedom to express ideas not commonly discussed or accepted in the society of his time.”

Boccaccio only describes the too-horrible realities of the Black Death (“mortal pestilence,” as he calls it) in his Introduction. “It is believed,” he adds, “without any manner of doubt, that between March and the ensuing July [of 1348] upwards of a hundred thousand human beings lost their lives within the walls of the city of Florence, which before the deadly visitation would not have been supposed to contain so many people!” But once the young people are situated in the country villa, they deliberately put the plague out of their minds and go on living, telling stories, and laughing.

Reading this masterpiece (I’m far from finished, with hundreds of pages to go), I’m reminded of many things: how important it is to read – and reread – the old classics that yearn to speak to us through the ages; how vital storytelling is to us all, especially in times of fear and uncertainty; how resilient human beings are and always have been. Florence survived the Black Death. I know this, firsthand, because I’ve been there. I celebrated my fiftieth birthday in beautiful, vibrant Florence, Italy, in May 1995. Alone.

So if Ramiro were to phone me today from Guanajuato to ask, como estas?, I’d give him this brief report:

San Miguel is quite quiet at the moment. Most of the tourists and snowbirds have left (in a rush). There are far fewer people on the streets and in the Jardin, and those who are out seem to be – amazingly! – following the Mexican health ministry’s new “Sana Distancia” [healthy distance] initiative. Schools, including the school where I volunteer-teach, libraries, and churches are closed. Musical, theatrical, and other cultural events have been cancelled. Restaurants, galleries, boutiques, and other tourist-dependent businesses must be suffering.

But, to date, there are no reported coronavirus cases in San Miguel de Allende and no deaths from it here – or anywhere else in Mexico — as far as I know.

And as for me, querido Ramiro, except for my daily walks in the park and weekly grocery shopping, I’ve been staying home. I’m reading a big, fat, wonderful old book filled with fabulous escapist stories. So, gracias a dios, and thank you for asking, I’m doing just fine.

And you?