In 1942, in the midst of war rationing, when many households had reason to fear “the wolf at the door,” an opinionated, highbrow beauty from California was the first American woman writer to publish a book that fearlessly included recipes to illustrate and augment her literary prose.

That audacious woman was M.F.K. (Mary Frances Kennedy) Fisher (1908-1992), and that book – one of the more than twenty books she published over the course of her literary career – was How to Cook a Wolf, which is still in print today.

In this collection of essays, each headed “How to […],” Fisher eruditely and forthrightly teaches her readers how to survive hard times and do so with style. And her simple, straightforward, step-by-step recipes, using readily available and affordable ingredients, provide solid proof that this can be done.

Like How to Cook a Wolf, which was its inspiration, my Peace Corps memoir-with-recipes How to Cook a Crocodile was written to be a guide for living healthfully and meaningfully under harsh conditions. At my Peace Corps post in the middle of Gabon’s equatorial rainforest, food was not rationed; but good, fresh food was really hard to come by. Cooking and eating well were daily challenges.

What Fisher’s book and mine mostly have in common, then, is that the item to be cooked in their titles stands purely as a metaphor for adaptation and survival.

Today’s coronavirus pandemic has been referred to as a war. So far, though, there’s been no wartime food rationing — that I’m aware of. But there are reports, at least in the U.S., that the food supply chain is “strained.” According to an article in The New York Times (April 13, 2020), “The nation’s food supply chain is showing signs of strain, as increasing numbers of workers are falling ill with the coronavirus in meat processing plants, warehouses and grocery stores.”

Restaurants everywhere are closed, many going out of business. Takeout options are iffy. We all may know, intellectually, that maintaining our health can only help strengthen our immune system and thereby fight this disease, and eating healthfully and well is one of the best ways of doing this. But, too often, quickie junk food – salty, crunchy, or sweet — with near-zero nutritive value, can win the day.

So the question becomes: If you can’t cook a wolf or a crocodile, what’s an inexperienced (or, perhaps, admittedly inept) home cook to do during a worldwide health crisis?

May I suggest: Learn?

Now may be the best time – because most of us have more time – to learn how to cook good, healthy, memorable food for ourselves and our families. We’re home – like it or not. Our kitchens are open for business. Grocery stores and pharmacies have not been shuttered. Cooking shows on TV and YouTube instructional videos abound. Countless cookbooks and recipes are available online.

You might even want to make your own cookbook and title it, “How to Cook Through a Pandemic” (or something like that), and turn it into a family heirloom.

“Good cooking,” I learned on the first day of cooking school in New York thirty-five years ago, “begins at the market.” First, you go food shopping, choosing what’s fresh and in season – and therefore most flavorful. Then you find recipes to suit those ingredients. Or you create recipes of your own.

I’m fortunate now, here in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, to be able to do my food shopping – my one big (well, only) outing of the week, wearing a face mask, of course — at the super-duper supermarket La Comer, which is just a two-mile walk from my studio apartment in el centro.

Comer (pronounced co-MARE) is the Spanish verb “to eat.” And this immense and impressively well managed store offers shoppers everything we could possibly need for cooking and eating well — and then some.

The store itself, by my wild guesstimate, is larger than a football field. It could house, I’m quite sure, at least one whole African village. In fact, I’ve often thought that if my African friends in Gabon could be somehow teleported to La Comer here, they’d think they’d died and gone to food paradise.

The ceiling is sky high, and light pours in from the clerestories. Its aisles are wide and sparkling-clean. The shelves are well stocked. The fruit and vegetables – all grown here in Mexico – are beautiful, colorful, and abundant. The young and helpful employees all wear face masks now, and the checkout clerks wear plastic face guards as well.

Since the local government instituted the sana distancia (healthy distance) guidelines, La Comer has marked its floors with large green arrows, indicating single-file, one-directional cart traffic. And there are now large, green, lily-pad-like circles on the floor near the registers, indicating where to stand to maintain a safe 1.5 meter distance.

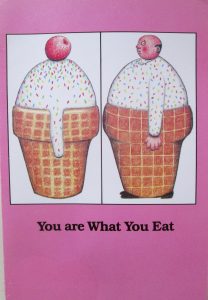

On my refrigerator here I keep a funny old greeting card that reads, “You are What You Eat.” It’s a daily reminder to me that I have a responsibility to do all that I can to stay well as long as I’m alive, and to be well I must make an effort to eat well. Cooking at home is empowering, so I start to employ that power every week when I do my grocery shopping at La Comer.

I’ll let M.F.K. have the last word here. She was, of course, writing during WWII, but her message applies equally to today: “Now, of all times in our history, we should be using our minds as well as our hearts in order to survive … to live gracefully if we live at all” (M.F.K. Fisher, How to Cook a Wolf).

~ ~ ~

(For a delicious, homey recipe for meatloaf, and a charming, timely story to go with it, go to www.eatdarlingeat.net and click on “Passing the Baton,” by Cherie Burns, published several days ago.)