Most graduates, I’m sure, can’t tell you the day after — much less years after — what the commencement speakers said at their graduation ceremony. In normal times, it all becomes a big blur of ill-fitting caps, swirling black gowns, solemn processionals, deep exhalations, and celebratory balloons.

But I remember clearly one commencement address because the man who gave it gave me a lasting gift.

At my graduation from the MFA program at Antioch University in Los Angeles on June 24, 2007, one of the commencement speakers urged us graduates to maintain a commonplace book. I’d never heard of such a thing, so I was intrigued and paid attention.

Keep a commonplace book from this point onward, he advised. Use it to write about each book that you read. Preserve what you learn from those books. They are your teachers….

He explained that commonplace books have a long and rich literary history. Neither diaries nor journals, which generally are chronological and introspective, commonplace books have been used for centuries by readers, writers, students, and scholars to help remember useful ideas or facts. Over the years, commonplace books have come to include any manuscript that an individual uses to collect material on a common theme.

So ever since my graduation from AULA thirteen years ago, I’ve followed that speaker’s advice and kept a commonplace book in which I write up the books I’ve read. Not really book reports or book reviews, these one- or two-page entries for me are more like responses: The book has spoken to me, and I choose to talk back. These write-ups are also a way to chronicle the books I’ve read. Otherwise, I fear I might forget them.

Now that I’m on my third volume of commonplace books, I enjoy looking back occasionally to see where I’ve been, literarily speaking: What books have I spent time with and welcomed into my mind and my heart? Where have these books taken me? How have they shaped my thinking, enlarged my soul?

Africa has featured prominently. My own four published books take place largely in Africa, a continent I love as if it were my adoptive mother, having lived there, in three different countries, for a total of nearly nine years. Many of the life-changing books I’ve read have been by African writers, such as Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard, and Trevor Noah’s Born a Crime; as well as memoirs by white authors born and raised in Africa, such as Alexandra Fuller’s Don’t Let’s Go to the Dogs Tonight and Cocktail Hour Under the Tree of Forgetfulness, and Peter Godwin’s When a Crocodile Eats the Sun and Mukiwa: A White Boy in Africa.

I’ve also striven to understand, through reading brilliant books by outstanding African-American authors, race relations in the United States, where the dynamics are far different from those in Africa. I’ve wished – no, required – these authors to teach me, to allow me to walk in their shoes (or their fictional characters’ shoes) as I walk through their books’ pages, to help me understand what it’s like to be the descendent of slaves and to be treated like third-class citizens in their own country, a country that professes equality for all. These books have permanently raised my consciousness on this vital issue.

Here, then, drawn from the more than three hundred books I’ve written up in the volumes of my commonplace books to date, in the order that I read them — and including their publication dates and a very brief summary — are the books I’ve read in recent years that have fulfilled these wishes for me. If you haven’t already read them, I would urge you to do so. Perhaps form a book group and use this short list as a starting point, or suggest this list to your existing book club. It’s never been more important to learn what books such as these can teach us.

And I wholeheartedly welcome your comments and additions:

- Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance (2004) – a moving and candid memoir of his early years, and The Audacity of Hope: Thoughts on Reclaiming the American Dream (2006) – based on his years in the U.S. Senate, both by Barack Obama.

- The Color of Water (2006) — a memoir of growing up in a black neighborhood as the child of an interracial marriage, by James McBride.

- Dust Tracks on the Road (1942) – an acclaimed memoir by the African-American writer whom Alice Walker called “a genius of the South,” Zora Neale Hurston.

- Wrapped in Rainbows: The Life of Zora Neale Hurston (2003) – an eloquent biography of one of the most intriguing cultural figures of the 20th century, by Valerie Boyd.

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (2010) – a brilliant chronicle of the decades-long migration of black citizens who fled the South in search of a better life, by Isabel Wilkerson.

- The Known World (2009) – this historical novel tells the story of a freed black man in Virginia who owns thirty-three slaves, by Edward P. Jones.

- Invisible Man (1995) – Ellison’s first novel won a National Book Award and established him as one of the key writers of the 20th century, by Ralph Ellison.

- All Our Names (2015) – a deeply moving story about a love affair between an American woman and an African man in 1970s America, by Dinaw Mengestu.

- Black Boy: An American Hunger (1945) – the story of Wright’s coming of age and development as a writer, by Richard Wright.

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1984) – this poetic and powerful memoir has become a modern American classic beloved worldwide, by Maya Angelou.

- Between the World and Me (2015) – this memoir, written as a series of letters to his teenage son, confronts the notion of race in America and how it has shaped American history, by Ta-Nehisi Coates.

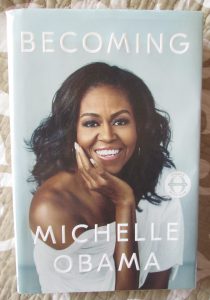

- Becoming (2018) – an intimate, powerful, and inspiring memoir by the former First Lady of the United States, Michelle Obama.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

P.S. – After having just seen the brilliant film “Just Mercy,” next on my reading list is the 2015 book by Bryan Stevenson, of the same title, from which the movie was drawn. As Michelle Obama says in her memoir, “Becoming is never giving up on the idea that there’s more growing to be done.”