Before I left for Gabon, Central Africa, in mid-1996, I had what I briefly thought was a brilliant idea. It was both a thought — an inspired one, I felt — and a gut feeling, not something I had spent time researching. (This, of course, was before Google was born). I thought I would introduce vanilla growing at my Peace Corps post and thereby single-handedly raise, exponentially, I felt sure, the standard of living of the people around me.

To the extent that I had thought this through, my reasoning went like this: Vanilla is a tropical plant; Gabon is a tropical, equatorial country. Vanilla beans are precious and costly; the poor people in the country’s interior would profit from growing and selling them. Why hadn’t anyone else thought of this? I wondered.

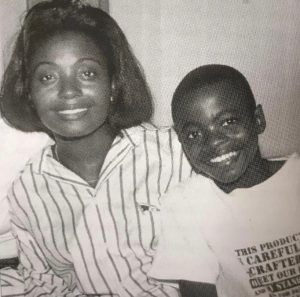

When I first shared these thoughts with my Gabonese “sister,” Yolande Borobo, with whom I lived during my Peace Corps training in the coastal capital, Libreville, and with whom I gratefully stayed during every subsequent trip from my post in the interior of the country, Lastoursville, to Libreville for my in-service training, she rolled her eyes and laughed.

“Vanilla? Here? Vanilla growing takes work,” she said to me in English, one of the several languages she spoke fluently, “hard, dirty work. And we Gabonese don’t like that kind of work. We don’t like to get our hands dirty. We prefer to work in air-conditioned offices.” She laughed again, flashing a gleaming smile and waving a manicured hand. “Oh, cherie, you’ll have to choose a better project than that. Ditch the vanilla idea.”

From then on, she called me her “Vanilla Sister,” a term of endearment that both fit and stuck.

Yolande, who worked in a modern, air-conditioned office as the private secretary for an oil executive in Libreville and whose work wardrobe consisted of fitted suits and tailored dresses she’d bought on her frequent trips to New York and Paris, was right, of course. Vanilla, I subsequently learned, is the most labor-intensive agricultural product in the world; and this was not the type of work the Gabonese preferred. Also, the soil and climate of Gabon were far from ideal for it.

My “inspired” vanilla idea, then, so utterly unsuited for Gabon, became a sisterly joke between Yolande and me — an example of how far off base a well meaning, utterly green, gung-ho, humanitarian-wannabe can be. But her nickname for me, Vanilla Sister, suited me, I thought, because compared to her Gabonese “chocolate” beauty, which never failed to turn men’s heads when we were together, I was indeed “plain vanilla.”

I remembered this – my vanilla-ness – especially this week when I heard Joe Biden’s words, “White Supremacy is a poison,” in response to the recent shootings in Buffalo, New York. That poison, tragically, has been sickening the United States for far too long.

I’ve been fortunate to have lived in three countries in Africa, on the ground, among Africans, for a total of nine years; and I’ve been living in the central mountains of Mexico now for close to seven years. In my experience in these countries, white people – or let me call us Vanilla People – are in the minority, and the concept of “White Supremacy” seems very foreign and, thankfully, far away.

I’ve been Vanilla all my life. I was born into a Vanilla family and grew up in a plain Vanilla town in northern New Jersey. Vanilla is okay. I’ve even experienced some of its advantages. Two small examples come to mind: When checks were offered as common currency, no one ever refused mine; and no one ever ran from me on a darkened city street.

But, happily, I’ve learned from my travels and my many friendships with people who do not look like me, such as my wonderful, generous, humorous Gabonese sister Yolande, that Vanilla is only one of many beautiful flavors in this world. There’s no reason why it should be supreme.

What, I worry and wonder, will it take for the dangerously misguided followers of White Supremacist ideology to realize this? I shudder to think they never will.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

The story about my Gabonese sister Yolande Borobo first appeared in my memoir How to Cook a Crocodile (Peace Corps Writers 2010). Some of the above was excerpted from the chapter “Vanilla Sister” in that book. To learn more, please go to: https://www.bonnieleeblack.com .