Ask any Returned Peace Corps Volunteer (RPCV) what the biggest, longest-lasting personal benefit of their two-year service overseas has been, and my guess is most will answer in one word: adaptability. Spin RPCVs around, toss them in the air high enough to drop them into another country, and they’ll likely, like cats, land on their feet and adapt to that new culture in record time. Why? Because we’ve learned how.

We learned how, I believe, early in our PC service, to let go of American expectations of what’s “normal.” That word quickly flies out the door of our cement-block houses or mud-and-wattle huts in towns and villages seldom shown on printed maps. “Normal” becomes a nonword, meaningless as a measure.

My favorite example of this comes from my experience in the middle of the rainforest of Gabon, Central Africa, where – after having given up a ten-year career as a caterer in New York City to join the Peace Corps at age fifty-one – I found my little house on the hill had no refrigerator. And I was unable to buy one.

As I wrote in my memoir, How to Cook a Crocodile (Peace Corps Writers, 2010), “If you live in equatorial Africa and you can’t afford a refrigerator, you might as well kiss butter goodbye. And fresh milk and cheese and ice cream and cold drinks and yesterday’s leftovers, too, just to name a few. This was the first lesson I learned at my new post: How to live, as one might put it in the lingua franca of francophone Africa, sans frigo (without a fridge).”

The trick, I discovered, petit a petit (little by little), was to shop for fresh foods daily and cook only as much as I needed that day — the culinary equivalent of carpe diem: Cook for Today. For me this meant walking every morning, after giving my health lecture at the hospital, the mile down hill from my house to the open-air marché in town to see what the women vendors there had to offer, then walking home in the hundred-degree heat to prepare my healthy soup du jour.

“I began to see,” I wrote at the time, “more and more clearly that not having a fridge was far from the hardship I’d at first imagined. In fact, it was a blessing, which, like so many of life’s blessings, had arrived disguised.”

Along similar lines, in my life here in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, I count the fact that I don’t have a car a blessing in disguise. For the vast majority of Norteamericanos, having a car in their garage is as necessary, as “normal,” as having a fridge in their kitchen. For me now, though, living as a retiree on a strict budget, being sin carro (without a car) is immensely better, and I’m grateful for it.

Need I list the health and economic benefits? I walk at least two miles every day in this beautiful old colonial city, under its clear, cobalt-blue sky, breathing its mountain air. If I need to ride somewhere in town, I can hail an ever-present green taxi to take me where I need to go for just a few dollars, or I can hop on a city bus for pennies. I’m spared the stress and expense of car ownership. I’ve been there and done that in my long life in the States. Never again.

Best of all, as I’ve been reminded recently, the intercity bus system in Mexico is superb. As Richard Ferguson writes in “All About the Buses in Mexico,” “The Mexican bus system is far superior to the U.S. bus system. Since fewer people in Mexico have cars, the buses are much more heavily used. This means that many buses are available to most destinations, from third class to luxury.” (To read the whole informative article, go to:

https://www.mexconnect.com/articles/965-all-about-buses-in-mexico/ .)

Lately I’ve been traveling by Primera Plus buslines to and from the capital city of this state, Guanajuato, for appointments and loving these luxurious yet super-affordable trips. With my half-price-for-seniors INAPAM card, a one-way ticket to, or from, Guanajuato costs me only 93 pesos (about $5 USD) for the one-and-a-half-hour ride. Far less than the price of gas, I’m sure.

The buses are clean, comfortable, and well-appointed, with Wi-Fi, video screens, leg rests, overhead bins, and a toilet in the back. It’s like traveling by air; but these big, modern buses are solidly hugging the earth. All of the passengers are masked, most doze or surf their phones. Everyone is quiet – even the babies. The bus’s motor hums.

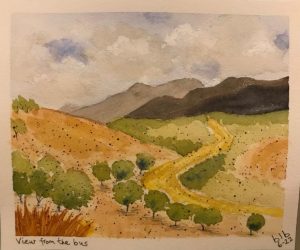

While others nod off, I sit at my window seat and take in the view from this high vantage point – Mexico’s astonishing body, her undulating mountains and piercing valleys; large patches of freshly tilled fields — the color of coffee-with-a-dash-of-cream — thirsty for the rainy season to begin; dramatic, puffed-up clouds elbowing out the sky’s blue, building, building…. In a week or two these brown fields will be baby-leaf green, and the scene will be altogether new.

I know if I were driving a car, focusing on the winding road ahead and the other cars whizzing past me, I would never really see these breathtaking scenes as they rush by.

Of course I’ve tried to capture this passing countryside with my camera, but only one or two of my photos have been worth preserving. And only one of them worth painting: