The word oasis has been reverberating in my mind lately. Such a beautiful-sounding word with such dazzling promise.

When things are looking bleak, we can scan the horizon and set our compass in the direction of our longed-for oasis. Or we can make an oasis for ourselves right where we are, such as many of us gringos here in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, are doing. Or we can be surprised by an oasis that arises like a dream to meet us on our journey.

Six years ago I wrote a WOW post (“Oases”) about an experience I had in Mali, West Africa, in late-2000 that fits into this latter category, which bears reposting, I feel. I was with a friend on our way to Timbuktu, and our car broke down in the Sahara Desert. Well, here’s the whole story:

[Oasis (n.): a fertile spot in a desert where water is found…]

When my dear friend Monty Freeman, an architect in New York, came to visit me in Mali, West Africa, in December 2000, we decided to go to Timbuktu together. I had been living and working in Ségou, Mali, for over two years by then and hadn’t done much traveling within the country. I knew I would likely be leaving Mali early in the new year. Who could say they’ve really been to Mali without having experienced its most fabled ancient city? So Timbuktu, for both of us, became a must-see.

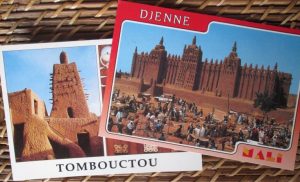

Monty hired a multilingual Malian tour guide, a sturdy car (SUV) and an experienced Malian driver, who’d made the trip to Timbuktu many times before; and we four set off. Monty, of course, had architecture on his mind, so along the way we stopped to admire the magnificent sunbaked earthen brick mosques that Mali is known for – especially the Great Mosque in Djenné, which is said to be the largest mud structure in the world.

Our drive was steeped in history. As we learned from our guide and Monty’s guide books, between the 15thand 17th centuries much of the trans-Saharan trade in goods — such as salt, gold, and slaves — that moved in and out of Timbuktu, passed through Djenné. Both towns became centers of Islamic scholarship. The population of Timbuktu swelled from 10,000 in the 13th century to about 50,000 in the 16th century after the establishment of a major Islamic university, which attracted scholars from throughout the Muslim world. Word of all this fueled speculation in Europe, where Timbuktu’s reputation shifted from being extremely rich to being extremely mysterious.

The drive from Djenné, in central Mali, to Timbuktu, which is nearly due north, takes more than eight hours and covers just over 300 miles – when all goes well. At some point the paved road disappears and one is left with sand as far as the eye can see. This is the Sahel – the “shoreline,” literally, of the Sahara Desert. Somehow, though, our able driver miraculously knew the way, despite no road signs or markers of any kind. Despite no signs of life anywhere — no trees or houses or little stores or even roaming goats. But Monty and I had faith. We chatted in the back seat and marveled at the monochromatic sandy scenery.

And then, suddenly, still some distance from Timbuktu, as the Saharan sun was beginning to sink, our car broke down. Our guide and our driver looked under the SUV’s hood and conferred in Bambara, Mali’s native language. Monty and I looked at each other silently, then studied the vast, undulating ocean of sand. The two men came back from their car-engine-inspection shaking their heads.

“Well, we can always sleep in the car!” I vaguely remember saying, merrily, to break the gloom.

Not possible, I learned. We had not come prepared for that. The desert, I was told, gets very cold at night, and we had no blankets. We could also be eaten alive by malaria-carrying mosquitos – not to mention other, unknown, unnamable deadly dangers. We sat and muttered.

And then, just as suddenly, as if literally dropped from the sky, there appeared an angel-like young man dressed in Tuareg robes, telling us, in French (Mali’s official language), “Come with me.” Monty looked dubious. I thought, “Adventure!”

We must have followed him on foot (I don’t remember getting into another car) for a while, until we reached his family’s compound (if that’s what you call a cluster of Tuareg tents staked out in the lonely desert). The young man introduced us to his father, the patriarch, who welcomed us warmly in French and excused himself abruptly because it was time for him to pray.

We watched as the old man, who looked to me like a miniature Santa Claus, rolled his prayer rug onto the ubiquitous sand, dropped to his knees, bent to press his forehead on the ground, and repeated the prayers he’d been faithfully reciting five times a day for well over half a century. When he was finished, and we explained our plight, he raised an arm, clicked his fingers, and told another of his sons who ran to his command to set up tents for “our guests” and to tell the women “we have four more people for dinner.”

By this time the sun had nearly sunk into the desert and the stars were about to take center stage. We ate outside under stars that seemed to multiply exponentially as the night wore on – so many stars I felt I could reach out and swoop them up into my hand. I was included with the men (perhaps because I had short-short hair at the time and was wearing long pants and the patriarch and his many sons didn’t know what to make of me?), sitting on folding chairs in a circle, with our tasty dinner of rice with a savory meat sauce served on large dishes in our laps. We spoke in French.

The old man had been following the news of the U.S. elections on Radio France. He knew all about “hanging chads.” He was stunned that Al Gore hadn’t won. He wanted to know what was wrong with America’s electoral system. I looked up at the stars, which were not that far away, and wondered whether I was dreaming.

The next day the old man saw to it that his sons had our SUV repaired, so we could be on our way. We made it to Timbuktu safely, and we were glad to say we saw that mythical city. But to this day Monty and I agree that more than anything in Timbuktu, we remember most vividly that kind old Muslim man and his oasis in the desert.

[Oasis (n.): … a pleasant or peaceful area or period in the midst of a difficult, troubled, or hectic place or situation.]