If I were still teaching Creative Nonfiction Writing at the University of New Mexico in Taos, I would assign this book to my students to read and study carefully, because I think it’s an excellent example of contemporary memoir writing done well:

Some people, I’ve found, confuse memoirs with autobiographies. To clarify: Autobiographies are stories of a life – written by (or ghost-written for) famous people who have a built-in following. Their fans have a deep-seated curiosity: How in the world did she (or he) become so famous? So they’re willing to follow that person’s story from cradle to however close to the grave this celeb might now be — all the ups and downs of that person’s life that led to their enviable fame.

Memoirs, on the other hand, are stories from a life. Not the whole life story, but rather the life-changing part or parts, drawn from the life of a regular, ordinary person who’s likely to be a stranger to the reader. It’s this writer’s story that pulls the reader in and takes the reader to places he or she has never been, broadening and enriching that reader in the process.

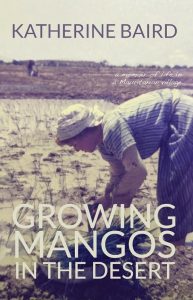

Katherine Baird’s memoir GROWING MANGOS IN THE DESERT, published last year by Apprentice House Press (www.apprenticehouse.com ), does just this and does it beautifully. It’s an excellent road map, in my view, and one that anyone who is interested in writing a memoir would benefit from following.

Many of the students in my Creative Nonfiction (CNF) classes at UNM were retired professionals who wished to use their suddenly free time to write their memoirs. But it took a while for them to realize this task would not be as easy as dictating letters to a secretary. Ultimately, they found they had to learn a whole new way of thinking and writing. This was not business writing, nor legal writing, nor medical writing, nor academic writing. This was something else.

The hallmark of CNF writing, of which memoir writing is a subset, is its conversational tone – amiable person to amiable person — as if conversing across a bistro table. It’s not haughty or preachy or lecturing. It’s not ego-driven. It’s not about puffing yourself up, it’s about sharing your shared humanity.

I’d stumbled upon GROWING MANGOS IN THE DESERT a few weeks ago, after doing research for my recent blogpost “Mango Season” (www.blog.bonnieleeblack.com/mango-season/ ). For a fleeting moment I thought I might want to take my passion for mangos to a whole other level and write a book about them. Instead, I was distracted by the title of Baird’s book, so I ordered it on Kindle and began reading it right away.

Katherine Baird, who is a tenured Professor of Economics at the University of Washington – Tacoma, began writing this book in 2012 as a eulogy for a man she’d come to know and deeply admire while living and working in the northwest African country of Mauritania decades before, when she was in her mid-twenties.

Distraught by the news of his death, she dug into her many spiral-bound notebooks from that period, long packed away in her basement, and began to write from her heart. The result is indeed a eulogy to that remarkable man, her friend and collaborator on her agricultural assignment, Mamadou Konaté, as well as a beautiful memoir of that challenging period in her life.

Here is my recipe for a meaningful memoir and why I think Baird’s contains all the main ingredients:

- Humility – Throughout this account, she is humble about her role, admitting she was ill-prepared for her job in Mauritania and having a lot to learn. So the reader is taken on a journey of discovery and growth. There is never any off-putting breast-beating or gloating.

- Patience – During her stay in Mauritania, she kept careful notes and wrote detailed letters home, all of which were saved for possible future use. Returning to them decades later, she was able to provide, as an older, wiser, well-educated woman, an even richer perspective and context in her memoir writing.

- Attention to detail – These notebooks and letters provided her with the critical information that memory likely would not have. Her writing is filled with vivid descriptions, solid details, and believable dialogue. As a result, the reader is able to see, hear, smell, and taste what life was like in that Mauritanian village. We are there with her.

- Craftsmanship – “Writers write,” I stressed to my students. This always includes prewriting (thinking, researching, note-taking), writing (doing many drafts), and rewriting (making multiple revisions). To achieve the kind of clear, honest, carefully written result that Baird’s book achieves, one must treat the writing as a craft and take the time and care it requires.

- Universality – On the surface a memoir might seem unique (Who of us has spent time in or even briefly visited Mauritania? for example), but underneath there should be a sense of shared humanity. When we get to know the people in her village of Civé – especially Baird’s friend Mamadou – our hearts and minds are opened to a broader world. One reviewer of Baird’s book referred to this as “globalization of the heart.”

- Teamwork – Sadly, too many contemporary memoirs, especially self-published ones, suffer from a lack of good editorial guidance. The adage “It takes a village” applies to writing a good book too. Baird’s editorial team at Apprentice House was clearly caring, painstaking, and professional. Her list of people to thank in her Acknowledgements is long, impressive, and inspiring.

I was initially drawn to Baird’s book by the mangos in the title, and I was pulled by them throughout. Where are the mango trees? I wanted to know. When will they start growing in the unlikely Mauritanian desert? She gives hints along the way, enough to keep my curiosity up, enough to keep me, like a fish hooked on a line, anxious to read on.

So without giving away any spoilers, I’ll just say that this book for me had a happy, satisfying ending.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

Following is an excerpt from the chapter “Home Above the River” in Katherine Baird’s memoir GROWING MANGOES IN THE DESERT:

As I entered their compound, I caught the lingering smell of smoldering charcoal and cattle dung. Ahead, four women stood beside a frail old man encased in a hammock and now struggling to emerge. Tin cans, handfuls of hay, plastic containers, burlap bags, various shaped gourds, and broken rubber slippers were scattered about.

Up I walked to the women. A thin matla [mattress] was produced and someone patted it to show I was welcome. I sat as Demba entered to explain who I was; word spread, and soon I was surrounded by a dozen villagers who now loudly proclaimed that I was the village’s new Americanaajo.

“Here, for you.” Demba was suddenly by my side and handing me a thick bronze key [to her hut]. “Time to head out.”

I stood and tried to say something, but my mouth went dry, and my legs felt weak. I looked about, then with a bit of confusion, followed Demba as he headed back to his truck. With his engine soon revving, Demba hung out the window and clasped my hand.

“Civé is a great village,” he promised me. Then he added: “It will be your new family.”

He put the truck in gear. I imagine I looked to him like an abandoned puppy. “They’ll feed you dinner,” he said while pointing beyond me to the compound where the old man in the hammock was now bent over but standing. Demba called out some blessings to him, then turned to give me one final smile. I tried my best to return his good cheer.

Then the truck lurched forward. Once again, Demba’s head emerged from the window as the vehicle continued on. With Baaba Maal’s loud but melancholy voice now filling the air, Demba hit the gas pedal, and left in his wake a growing dust cloud, a rising mass of cheering kids, and one deserted Americanaajo.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

For more about GROWING MANGOS IN THE DESERT, please go to Katherine Baird’s website: http://kebaird.com/kebaird-author/