“Art’s meaning begins with seeing and experiencing the work itself,” writes artist Kathleen Cammarata of her current solo show, “What We See … What We Don’t See,” at the Museo de Arte de Queretaro. “We bring to images our life experiences,” she writes. “We choose what we see.”

This week I chose to make a day trip to the historic district of Queretaro from San Miguel de Allende to see Kathleen’s breathtaking exhibition of drawings, paintings, and mixed media and to share some of what I saw and experienced with my many WOW readers. If you are fortunate enough to attend the exhibition in person, it will be up until June 22. The museum’s hours are 10 am to 6 pm, Tuesday through Sunday.

WOW readers may recall my interview with my friend and “homegirl” Kathleen of June 2022 in her studio here in San Miguel (https://blog.bonnieleeblack.com/Kathleen-Cammarata-painting-connections/ ). In this wide-ranging interview Kathleen told me her ultimate goal was to have her paintings in a museum one day. Now you can find her glorious paintings – in this magnificent museum:

The Museo de Arte de Queretaro is located on Calle Ignacio Allende Sur 14, in Queretaro’s downtown historic district, about 1-1/2 hours from San Miguel.

In the entryway to the museum: Admission is free and the museum’s hours are 10 am to 6 pm, Tuesday through Sunday.

This magnificent 18th century Baroque-style cloister, one of the most beautiful in Latin America, became home to the Museo de Arte de Queretaro in 1988.

Inside the exhibition: two grand rooms of Kathleen’s drawings, paintings, and mixed media.

What we may not see at first glance in this painting, “Anticipacion,” is the contemplative woman at the center of it.

Many of Kathleen’s paintings and drawings feature women, in all their beauty and mystery.

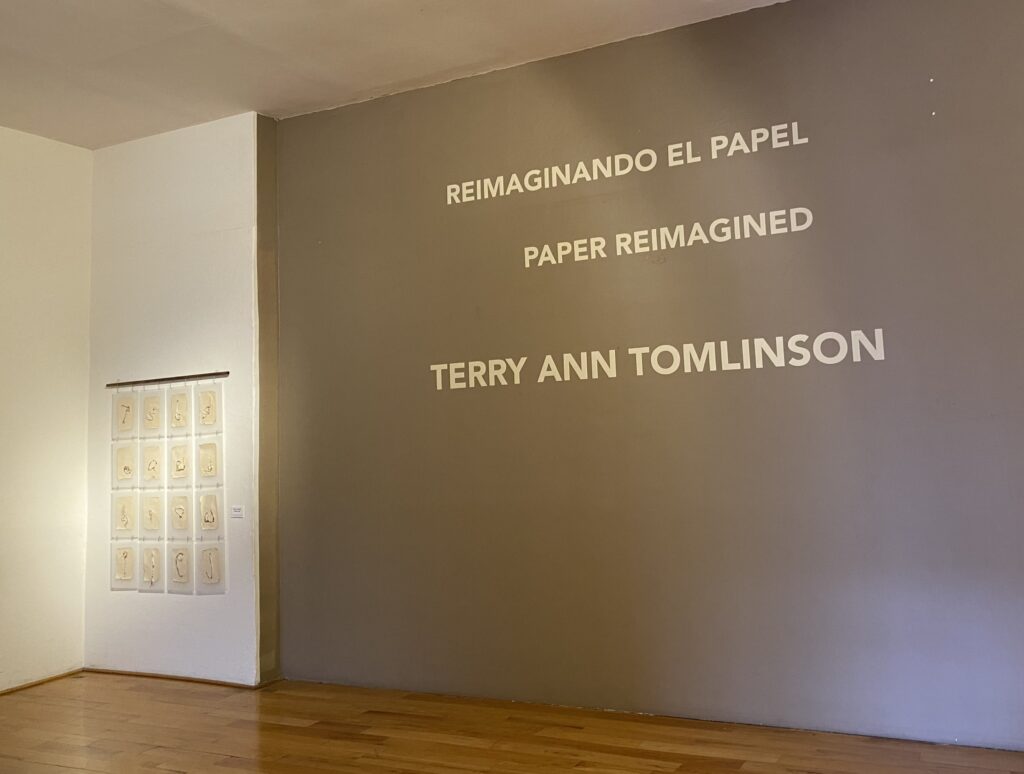

As I was leaving the museum, I noticed another remarkable exhibit by another mature woman artist from San Miguel, “Paper Reimagined” by Terry Ann Tomlinson, which will be up until May 18th. So if you visit the museum before then, be sure to see both!

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

For more information about Queretaro, go to: www.queretaro.travel.

For more information about Terry Ann Tomlinson’s work, go to: www.terryanntomlinson.com.