I, along with many others, I’m sure, have often wondered, What would I have done if I were there? I was born in the U.S. just after WWII, but what if I’d been German living in Germany during the Holocaust. What would I have done?

Would I have kept my head down, gone on with my little life, ignoring the signs, the rumors, the fumes? Would I have naively trusted the authorities – political and religious – believing they knew best? Would I have gone along to get along, not wishing to stick my neck out, raise my voice, step out of the secure circle of my small, cherished community? Would I have clung to my known and comfortable life path out of, what? Fear? Apathy? Lethargy?

I like to think not.

I am half German. My mother’s parents were German immigrants to the United States, and my father’s parents were from Scotland. Although my mother’s family had nothing to do with the Holocaust, having emigrated from Germany before the First World War and they soon stopped speaking German and completely acclimated themselves to the American way of life, I’ve always been ashamed of that half of me. How could I be even remotely related to such a cold and heartless people who allowed the Holocaust to happen?

All my life, as is my want, I’ve searched for answers to these questions, in books and films (such as “Schindler’s List” and “The Boy in the Striped Pajamas”), as well as in true personal stories. I’ve longed to be inspired by stories of heroism, such as this story my French friend Marie-Laure told me about her father:

During WWII he was a policeman in Paris, and his beat was the 16th Arrondissement, which included countless elegant apartment buildings owned by Jews. When he became aware that Jews in the city were being rounded up and sent away, he quietly and privately warned the Jewish landlords whom he knew of the dangers they faced. Many of them fled to safety with their families and friends before they could be captured. In providing this warning, Marie-Laure’s father alone, a Catholic man in his early twenties, saved perhaps hundreds of French Jews’ lives.

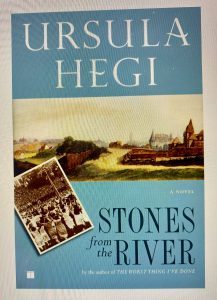

And books. One book in particular stands out: Stones from the River, by Ursula Hegi, published in 1997. This novel opened my eyes to small-town life in Germany during that war. The lesson I learned from this powerful book about one small person’s heroism stuck with me for years (and I’m now rereading this gripping story):

Trudi Montag and her father, a widower, own and run a bookstore in the German town of Burgdorf. Trudi is indeed a small person; she is a Zwerg – a dwarf – so she knows discrimination first-hand. Her loving and tender father, however, teaches her that the most important thing in life is to be kind. It is here, in the cellar of their home, beneath the bookstore, that father and daughter harbor their Jewish neighbors to save their lives.

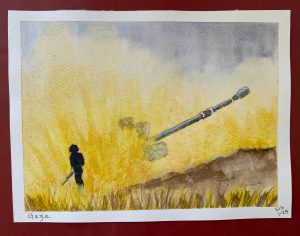

Today there is a new war raging, with a new genocide in the making. I ask myself, What can I do? I know I cannot ignore it. I cannot turn away from it. Yes, it’s far away, in the Middle East, on the other side of the world. But my country is supporting it – aiding and abetting it – so it is in fact close to home for me. I cannot be apathetic. I believe apathy is complicity.

Speaking for myself, I’ve decided I must learn as much as I can – pay attention to truthful speakers, read trusted news sources and good books – and then share what I learn wherever and however I am able.

As a writer, I consider myself a messenger. So, for example, if I see a video of an old, white-haired-and-bearded rabbi crying out from his heart about the horrors of this genocide – “This is NOT who we are as Jews! This is not what the Torah teaches!” – I hear the truth of his words and consider it my job to share his message as widely as possible.

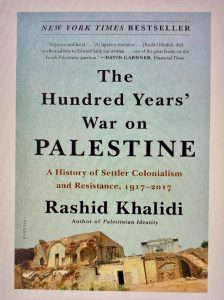

As a teacher (still, at heart), I must press meaningful reading matter on whomever I can reach. This book especially, which I just finished reading, is a must for anyone interested in this current war: The Hundred Years’ War on Palestine, by Rashid Khalidi, published in 2020. This brilliant book, a New York Times bestseller, which was recommended to me by a Jewish friend, is not an easy or quick read. But it is well worth the time and effort. It puts things in perspective. It answers questions and even offers some hope.

As an American citizen, I’ve written to President Biden to let him know my stance. Will he read it? Will it matter? Doubtful. But I still have a voice, and I’m still free to use it. The U.S. is still a democracy, isn’t it?

As an older, single woman, I no longer care what people think of what I say or write or do. That’s one of the many beauties of this age and stage of life. I cannot lose my job by speaking out, because I’m retired from the workforce and nobody pays me to write or speak. I cannot upset my husband by taking a radical stand, because I don’t have a husband to tell me how to live. I am free to be me now, and I’m thankful for that. I have “nothing left to lose,” as Janis Joplin used to sing.

Two weeks ago, on New Year’s day, I woke before dawn to watch the sun rise on this new year. I took a photo of that dramatic sunrise, and I wrote this quasi-poem to express how I felt in that moment:

If enough of us who ache for peace

put more pressure on the Powers that Be

while we still have a voice (Democracy?),

perhaps, just perhaps,

we might see peace in this new year.

We need not be passive observers

to this ongoing horror show,

as if it were a dream we couldn’t wake from.

We must wake up, get up,

and put our shoes on.

For me, the worst thing I could do now would be to turn away, cover my eyes, ears, and mouth (“See no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil”) because it’s all so upsetting and unpleasant, and be like those Germans during the Holocaust who did nothing – to their eternal shame.