My posts of late have been mostly “views” – short essays (opinion pieces), observations, and musings on whatever has managed to capture my interest or trigger my memory that week that might pertain to the lives of older women. Being an older-woman writer now, having reached this vantage point, I feel it’s incumbent on me to share my views from time to time – for whatever they’re worth – with those who are still on their way.

This week, though, one older American woman has made headlines all over world for doing what no other woman has ever done: become nominated by a major political party for the presidency of the United States. This is indeed newsworthy. This is not just my view. This is earth-shaking NEWS.

Hillary Clinton, 68 years old, mother, grandmother, former First Lady, former New York State Senator, former U. S. Secretary of State, is now on her way (many of us hope and pray) to becoming the first woman U.S. President. I suggest we all observe a moment of silence to think about that fact. And in that moment of silence we might reflect on just how far we’ve come in the space of Hillary’s (and my own) lifetime.

I have a vivid memory of seeing in an issue of National Geographic one day when I was about nine or ten (circa mid-1950s) a photo of a woman doctor in Russia. “Woman doctor?” I thought then, stunned. “You mean women can become doctors?!” At that time, in the suburban New Jersey world where I lived, women couldn’t be doctors! They were housewives, like my Mom, in aprons, or teachers in our grammar school, or nurses at the local hospital. Not doctors!

A woman then was “the little woman” spoken of (condescendingly) by her Father-Knows-Best husband. Women were passengers in the vehicles driven by their husbands (or fathers), who held tightly to the keys. They were secretaries being dictated to by their (always male) bosses.

I get the impression that Hillary’s scary Republican opponent wants to return the U.S. to that time. He wants to turn back the clock to the “rosy” fifties. Ha! Rosy for whom? Certainly not for women; and, therefore, not for the world.

Last night, as I watched on CNN Hillary Clinton give the speech of her lifetime, capping the four-day, well-choreographed Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia, I was in awe. To me, she looked more beautiful, radiant, and confident than ever. Although she’s been knocked down, beaten up, maligned by a mad man (“Crooked Hillary!”) and essentially torn to shreds, she’s gotten up and gone on, with grace, intelligence, and maturity. Last night, as I watched and listened to her closely, her broad, sincere smile spoke volumes about her seemingly unbreakable strength of character.

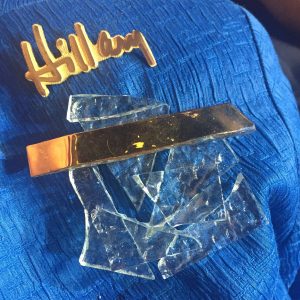

Is she flawless? No. Is any human being, man or woman, perfect? No. Is she a new role model for little girls and young women, not only in the U.S. but all over the world now? Yes. Has she broken through a significant glass ceiling, for which all forward-thinking people should celebrate? Yes. Will she break through another, higher glass ceiling this November and win the election to become the first woman President of the United States of America? I’m confident that with the powerful backing of all those – especially us women — who are jubilant that we are no longer living in the repressive 1950s, the answer to this question will be YES.