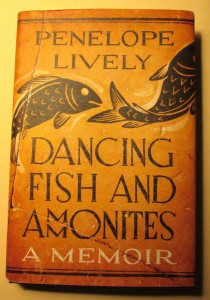

If I were to press one book on my women friends today – especially those friends who belong to women’s book groups – it would be this one, which I read recently: Penelope Lively’s memoir Dancing Fish and Ammonites (Viking 2013).

By chance, I’d caught Lively’s interview with NPR’s “Fresh Air” host Terry Gross on March 17, which happened to be Lively’s 81st birthday. (To hear the interview, go to: http://www.npr.org/2014/03/17/290855933/author-penelope-lively-shares-the-view-from-old-age.) And I was so enchanted with Lively’s voice and her views, I immediately bought her new book.

Author of 22 acclaimed novels and several works of nonfiction, Lively shares in this her latest work her perspective from 80. And what a refreshing, uplifting perspective it is. Reading this memoir, I felt as if I were an honored guest in her London home, where I was able to admire her personal library of over 2,000 books, as well as her favorite objets d’art, and listen to her life stories in the context of twentieth-century European history. I was entranced. I never wanted our visit (her memoir) to end.

In the chapter “Old Age” she writes matter-of-factly about the things she’s had to relinquish due to advanced age, such as beloved gardening and long-distance travel. But at the same time, she celebrates the things she still holds dear, especially writing and reading.

“For me,” she says, “reading is the essential palliative, the daily fix. Old reading, revisiting, but new reading too, lots of it, reading in all directions, plenty of fiction, history, and archaeology always…” She calls reading her “one entirely benign mind-altering drug,” despite the fact that she suffers from macular degeneration.

“Others may have a game of bowls, or baking cakes, or carpentry, or macramé, or watercolors. I have reading,” she says.

She admits to no longer being acquisitive at this age. She may admire things, but she no longer covets them. But: “Books, of course, are another matter; books are not acquisitions, they are necessities.” However, there are a few priceless things in her possession that she cherishes and writes about at length.

One is a potsherd, about four inches across, the fragmented base of a shallow dish made in Egypt (the place of Lively’s childhood) in the twelfth century. The glaze on the sherd is a rich honey color, she tells us, and on it dance two small black fish. She writes:

“A friend gave me the sherd, twenty years or so ago, and it has sat on my mantelpiece ever since, relished for its survival, for its provenance, because it says that a potter a thousand years ago had seen fish leap, because it has traveled through time and space like this, ending up in twenty-first-century London, a signal from elsewhere.”

Another of her cherished objects is even older by far. It is “a sea-smoothed flat pebble of blue lias, itself just larger than an opened hand” which she picked up on the beach in Dorset many years ago and into which are embedded “two little curled shapes, an inch across”: ammonites, marine invertebrates, millions of years old.

“Paleontology is awe-inspiring, sobering,” she says. “Deep time. It puts you in your place – a mere flicker of life in the scheme of things. I take note of that whenever I walk on one of the north Somerset beaches.”

Lively doesn’t say this, of course – she is a novelist, after all, who allows her readers to draw their own conclusions and make their own connections – but for me the implication of the fish sherd and fossils of the book’s title is that however small we may be, we might still somehow leave a lasting impression on this earth. — BLB