There’s a Jewish concept that all of us would benefit from following, regardless of our age or religious beliefs, I believe. It’s called “tikkun olam” in Hebrew, and it means “repair the world.” I learned about tikkun olam this week when I interviewed the remarkable Judith Jenya, at her home here in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico.

In her long life journey — she is now 82 — Judith has been many things: wife, mother, art teacher, art therapist, photographer, psychotherapist, attorney in private practice, world traveler, lover of adventure, spiritual seeker and questioner, painter, peace activist, and more recently, memoirist and poet. Above all, she’s been a selfless and award-winning humanitarian, living her deep belief in tikkun olam.

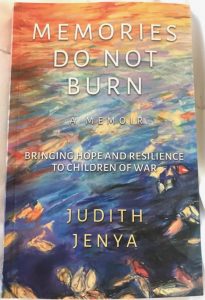

At the end of her riveting memoir, Memories Do Not Burn: Bringing Hope and Resilience to Children of War, published last year by Picacho Press, Judith states that tikkun olam, as a personal responsibility, “is as close to a metaphysical or religious calling as I have ever known. I feel it in my bones. I’ve lived with a sense of responsibility to attempt to heal part of the world with which I am engaged.”

Following are excerpts from my long one-on-one interview with Judith this week:

BB: As I ask all WOW interviewees, what would you say is your greatest accomplishment so far?

JJ: My greatest accomplishment is Global Children’s Organization, which I founded and directed for a dozen years and which served about 1,600 children in my various summer camps. It was a life-changing experience for most of them – and for me. And we’re still connected.

BB: Where were these camps and what was their purpose?

JJ: They were mostly in war-torn areas of southeastern Europe – Croatia, Bosnia, Serbia – as well as in Northern Ireland; Los Angeles, California; and Taos, New Mexico.

I began GCO in the early ‘90s in the hope that this program would heal the children and give them hope in spite of the shattered world around them. I believed strongly in social justice, and this was putting my beliefs into action. It was a profoundly spiritual experience to work with these children and the 400-or-so volunteers. It was a miracle. It was a dream come true.

BB: How did GCO come about?

JJ: When I was fifty – recently divorced, living in Honolulu, my two children basically grown – I was invited to help run a youth camp for children outside of Moscow. I was a lawyer in private practice at that time, and I represented children a lot. So I said “Yes.”

Basically, when people ask me, “Do you want to do such-and-such?” or “Can you do such-and-such?” I generally say “Yes.” That’s been my M.O. my whole life. I always say yes. My motto used to be “Leap before you look!” But I’ve toned that down with age. I just don’t think in terms of “No.” Even the Russian word for “no” – “nyet” – means “Not yet” to me.

So that’s how it all began. I set up Global Children’s Organization, and with a lot of amazing occurrences, it happened. We had a broad portfolio of activities so that GCO could do just about anything pertaining to the well-being of children. We had a small board of directors and a network of friends who supported me and the goals of the organization.

BB: Let’s bring this up to the present. You recently returned from a big trip to that region. Could you tell us a bit about that?

JJ: Yes, last month I was in Malta, and I stayed with a woman from Serbia whom I had not seen since she was twelve years old when she was at one of my camps. She is now a psychologist in Malta working with refugees, and she said that I was the inspiration for her work.

I’m always glad to know that my example has motivated other people to take action. I’ve learned of people in other countries who have started camps similar to mine. I always help them if they ask. Currently, I’m sharing my experience with a nonprofit in Ukraine called Voices of Children that focuses on the psychosocial aspects of war and how it affects children. I feel I am continuing my work.

I think that one of the issues we have in the United States and around the world is that the common good is not thought of enough. People think about themselves but not society, and you can’t maintain a society where people don’t care about the common good.

BB: You are 82 now. What keeps you going? What motivates you?

JJ: First of all, I’ve created this lovely haven here in San Miguel – this house, this garden, these animals, my husband Mark, whom I married in 2011. I can do what I want now. I have freedom. I can select. During the pandemic I learned pastel painting, and now I’m trying to learn watercolor. I write poetry. I have a bilingual book of poetry in addition to my memoir Memories Do Not Burn.

When I was a young girl my mother took me on a road trip through Mexico. One of the stops we made was in a little mountain town called San Miguel de Allende that harbored an art school and a small artists’ colony. In that brief visit, I dreamed that someday I would become an artist and make my home in San Miguel. My life and travels have now come full circle.

I feel very blessed to be living in San Miguel. I feel very glad to be out of the maelstrom that is the United States now.

I’ve always been an adventurer, and I’ve had many adventures all over the world. This trip last month in May was a really big deal for me. I was leery about it at first because I have some health issues. But I still believe in the kindness of strangers, and it works, actually.

There was a lot of changing planes to get there, but I always use a wheelchair in each airport, so somebody is always getting me to the right place, making sure I get on the plane. You go zipping through Customs, you go zipping through everything! It’s a blessing. Also, I paced myself on this trip, rested a lot, and stayed hydrated.

After Malta I went to Sicily. The last day I was there I decided to visit Mt. Etna. So I hopped on the back of an ATV, wearing a helmet, bouncing up and down…. I thought, “Am I crazy to do this at my age?” And then I thought, “Never say never.”

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

[Following is an excerpt from Judith’s memoir:]

The smell of onions and unwashed bodies filled my nostrils as I entered the crowded refugee camp outside Split, Croatia, in April 1993. This was my first experience of a refugee camp. I was overwhelmed…

Then I saw a small, blond girl with sorrowful blue eyes. She wore a stained blue and red pinafore and just stared disconsolately at the floor. I had learned a few words of Serbo-Croatian, and I asked her, “Kako se zoves?” (What is your name?)

In a hushed, weary voice she answered, “Nada.” Suddenly it was California, 1948. I had met a dark-eyed, dark-haired girl, much smaller than the one before me. She had deep circles under her eyes, a sad smile on her face. Her parents pushed her forward to meet me.

My father said to me, “This is Nada. She is going to share your bed for a while. Her younger sister, Etty, will sleep on a cot by your bed.”

I asked, “What kind of name is Nada?” Many kids in my neighborhood spoke Spanish. I knew that “nada” meant “nothing” in Spanish.

My father told me, “In her language, nada means hope.”

Now I looked through my tears at this little girl in front of me. I realized that the Nada of my childhood was my first step in my journey to bring hope to people caught in war and intolerance.

I reached out my hand to this Nada in the refugee camp and gave her a smile. I knew that hope was the one thing that my fledgling organization, Global Children’s Organization, could offer children who were the youngest and saddest victims of the genocide in the former Yugoslavia.

I thought of the principle of “tikkun olam.” Each of us is charged with repairing parts of our shattered world and to help make it whole – with care and compassionate action. … I knew that I had been called, and I had to answer. I also knew that even as just one person, I could make a difference for children in this horrible war.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

To order your copy of Judith’s memoir, Memories Do Not Burn, go to Amazon.com or to her website, www.judithjenya.com .