Sometimes, I’ve learned along the way, a teacher has to get to the cold, hard truths of a subject by taking a warm, soft, roundabout route. I think of Emily Dickinson’s words, “Tell all the truth, but […] success in circuit lies….” Run in circles. Tell tall tales. Make a fool of yourself. Cast a spell. Captivate.

This was the challenge for me this past Wednesday when I taught my afterschool class of thirteen-year-olds here in San Miguel de Allende. These are bright, highly motivated Spanish-speaking Mexican kids whose English is admirable. My lesson plan was to tackle the current, deadly-serious subject – the coronavirus pandemic – in a roundabout way.

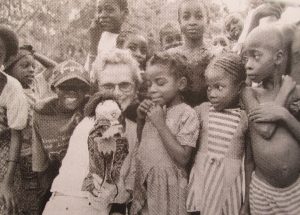

I began far afield by telling them about my Peace Corps service in Gabon, Central Africa, twenty-four years ago as a health and nutrition volunteer. Gabon, I showed them on the map of Africa, is on the Equator. “Hot-hot-HOT!” (I fanned myself.) “Lots of RAIN – and BUGS – and MUD!” (I gestured madly.) “Too many terrible illnesses, like malaria and dengue fever.” (I made a sick face.) “So my job was to teach people – mostly mothers and children – how to do what they could to stay healthy.”

I looked out over the class of Mexican kids. So far, so good. They were with me. I spoke slowly and clearly, making sure I didn’t leave anyone behind in my dramatizations.

“One of the ways I taught the African kids,” I said, “was with puppets!” (These kids already knew my passion for puppets, so this wasn’t news to them.) I showed them a photo of my handmade puppet “family” in Gabon and another photo of me with my most popular puppet then, Chantal Chanson, who became something of a rock star among the Gabonese children, especially with her hit tune, “Lavez les mains.”

Then I sang for them Chantal’s song (truly making a fool of myself) and taught the class to sing it too, in French (“because Gabon is a French-speaking country,” I explained): “Pour avoir la bonne santé, lavez les mains, à l’eau et au savon!” We then translated it into English (“To have good health, wash your hands with water and soap”), then into Spanish.

Getting serious now, I picked up the small globe I take with me to class each week, twirled it in my hands, and asked them about the health problem facing the whole world right now.

They already knew.

“It seems to me,” I said, “that as humans we always have choices. In this case, we could choose to be sad about this situation [I drew a sad face on the board, pretended to rub my eyes and cry], scared [I drew a terrified face and made one myself], or smart [I drew a calm face and tapped my right temple]. Which would you rather be?”

They all opted, of course, for the latter.

I reminded them of our lesson from the week before on “How We Learn” and the “Question Words” to use to learn new things — the words that Rudyard Kipling called his “six honest serving men,” that “taught him all he knew”: What, Where, Why, When, How, and Who. Then I applied those question words to the coronavirus, eliciting answers from the students, such as:

What is it?

A new and mysterious disease.

Where is it?

All over the world, but especially in China, Iran, Korea, Italy and other places in Europe.

Why should we be concerned?

Because it’s spreading fast. There are not many cases in Mexico right now, but that could change quickly.

When did it start?

Recently – just a few months ago.

How can we help prevent its spread?

By following the experts’ advice – social distancing, frequent hand-washing, avoiding touching one’s face, staying informed and vigilant, but not panicking.

Who should do this?

All of us!

We then practiced some social distancing methods and even turned the exercise into something of a dance routine: touching each other’s shoes, bumping elbows, bowing… The kids laughed.

Then I pulled from my big bag a large plastic bowl, a bar of soap, and a roll of paper towels and simulated hand washing (without water) on a table in front of them.

“Did you know,” I asked, rubbing my hands, “that we should wash our hands for 20 seconds?”

They didn’t.

“How long is 20 seconds? Is it 1-2-3-4-5-6-7…?” I rushed through the numbers.

They shook their heads.

“Right! It’s more like: one banana, two bananas, three bananas, four bananas…” They laughed even more. “So count with me, as I pretend to wash my hands.”

They counted twenty bananas, laughing the whole time.

Then I had a few of them come up, one by one, and do the same – only they could choose the three-syllable noun that all of us would use for counting the seconds as they demo’d washing their hands: “one papaya, two papayas, three papayas…” or “one elephant, two elephants, three elephants…”

These kids are impressively aware of current events, and their worldview is wide. I like to think, though, that those twenty bananas were new to them, and they’ll think of them often as they thoroughly “lavez les mains.”