Sixty years ago, on March 1, 1961, President Kennedy — heart throb to me and all of my fellow teenage girlfriends at the time — established the United States Peace Corps.

I was not among the thousands of idealistic young people who flocked to answer JFK’s call to “Ask not what your country can do for you — ask what you can do for your country” and sign up for Peace Corps service. No. In characteristic glacial fashion, I took a lot longer. I was fifty years old when I joined.

Looking back now, I can see it was a risky decision, for which I was rightly criticized by some friends and family. For one thing, if I hadn’t dropped out of the work force for two years to become a Peace Corps volunteer in Gabon, Central Africa, from 1996-98 — and subsequently do independent volunteer economic development work in Mali, West Africa, for three years — I would be receiving more in monthly Social Security payments now that I’m old and retired. That would be nice, of course.

But to me, for better or worse, other things, things that cannot be numerically calculated, have always been more important.

I found my Peace Corps experience, in a word, priceless. Okay, I know it’s a cliché, but the memories I have of those two years of serving as a health and nutrition volunteer in the little town of Lastoursville, Gabon (and later living and working in Ségou, Mali), are worth more to me than gold. Or diamonds.

For those unfamiliar with the system I’ll explain that the “Third Goal” for RPCVs (Returned Peace Corps Volunteers) is to share our experiences overseas with people back home in the States after returning from service, in an effort to help expand everyone’s worldview a bit.

But I’ve found over the years that very few Americans care to listen to or read about others’ true Peace Corps stories. Fellow RPCVs have their own stories, which they favor; and almost everyone else tends to roll their eyes in pre-boredom at the prospect of learning the “goody-goody’s” tales of “adventures” in the back of beyond.

Nevertheless, I stubbornly wrote a whole memoir-with-recipes about that exciting, enriching, life-changing chapter of my life, titled How to Cook a Crocodile (Peace Corps Writers 2010). Here is a short excerpt from that book, just one in ten thousand memories of that time, to give you a tiny taste of Peace Corps life then in Francophone Africa:

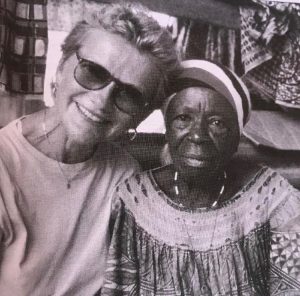

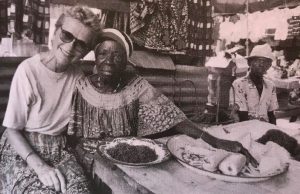

One day, early on, one of the marchandes there, a tiny, wizened woman of about eighty, whose small table sat alone near the entryway to the marché, commented on the long, blue denim A-line skirt I was wearing. She said, half-teasingly, in French I could grasp, “You could dance the tango in that skirt.”

“Well, then, let’s dance!” I said, so she gamely got up from her wooden bench and we danced a little mock-tango, for everyone’s enjoyment, right there beside the piles of hot peppers and plantains.

She told me her name was Leora. On a large, round, enameled tray in front of her she sold sandwiches made from chunks of locally made French bread that she slathered with margarine and filled with thick slices of what she called saucisson but what looked to me like plain bologna.

Every day, after I’d made my rounds, up and down the aisles of skimpy produce offerings, Leora would pat the bench beside her and invite me to “rest my legs.”

I sat close to her, close enough to take in the elemental odors of her threadbare clothing and leather-like skin. She smelled to me like fire and earth, wood smoke and loam. She smelled of Africa, and I drank it in.

I sat beside Leora at the marché every morning, and over time, in clear, slow, patient, motherly French, she shared with me stories about Lastoursville and her life.

She told me about the arrival by river of missionaries to Lastoursville, when she was a little girl. She mimicked how straight and somberly the missionary wives sat in the dugout canoes – there were no good roads then, she said – and how these rigid white women wore huge white hats covered in netting to their necks, to keep the sun and bugs off their delicate white skin, and how they had to be carried overland in palanquins because they didn’t want to muddy their high, buttoned, white leather shoes.

She told me about her married life in the lively coastal city of Port Gentil, where her beloved late husband had been a proud policeman, and she had worked as a cook and seamstress for snooty – she flicked her nose with an arthritic forefinger – French women.

Her dream, Leora told me dreamily, was to return to Port Gentil one day, to recapture those happy times and breathe salt air before she died.

When I asked her whether she and her husband had had any children, she shook her head sadly. “Non.”

Leora was unusual in this and many other ways. Not only was she truly elderly – decades older than the fifty-two-year life expectancy for Gabon – but she lived alone. She had no family. She had traveled beyond Lastoursville, she was literate, and she spoke fluent French. She was independent: She supported herself entirely by selling her homemade saucisson sandwiches. And every morning, regardless of the weather, she walked almost a mile to and from the marché in bare feet. …

Oddly, in many ways Leora reminded me of my own mother, whose name was Lee and who would have been close to Leora’s age if she were still alive. Both women were small, thin, and strong as a sailor’s rope; both were a rare blend of spirited and shy, funny and cynical, vulnerable and sinewy. And they both looked at me similarly, with a singular focus, as though I were the most fascinating and baffling creature they had ever seen.

So in Gabon, Leora became my maman. We adopted each other, unofficially. Wordlessly, somehow we agreed that she could depend on me. For as long as I lived in Lastoursville, I would care for her if she fell ill, the way I’d cared for my own mother when she was dying of cancer. And Leora, for as long as she could, would be there at the marché for me – welcoming me with a smile, patting the space beside her, urging me to rest a while, and looking at me wonderingly, as if to ask, Where did you come from?

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

For more on my Peace Corps experience in Gabon, please go to my website’s Home page and scroll down to How to Cook a Crocodile: A Memoir with Recipes: www.bonnieleeblack.com.

And for much more about the U.S. Peace Corps, please visit: www.peacecorps.gov.