To quote Yahoo News this evening, “Millions of people took to the streets Saturday in ‘No Kings’ marches opposing President Trump, with demonstrations unfolding in more than 2,500 cities across all 50 states and several European capitals.”

San Miguel de Allende, here in the central mountains of Mexico, is not a European capital, but our “No Kings” rally on this typically beautiful day, in front of the U.S. Consular Agency at the Luciernaga mall, certainly added to the world’s numbers of “No Kings” demonstration-goers by hundreds.

(The “No Kings” crowd seemed to fill almost the length of a city block at the Luciernaga mall)

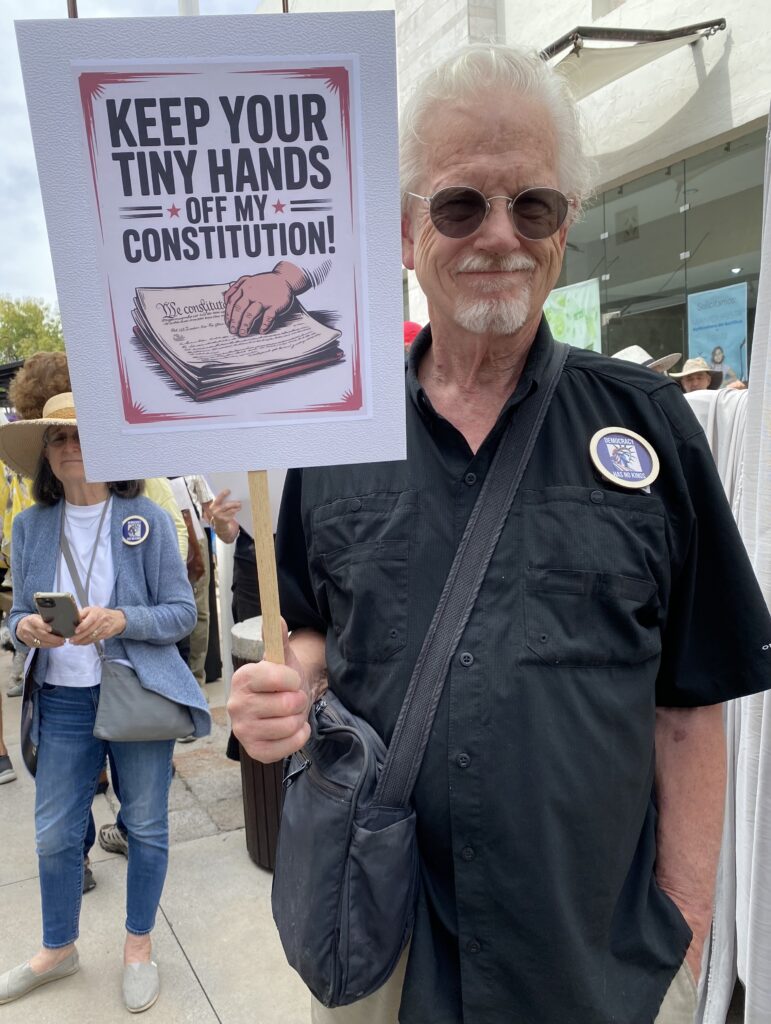

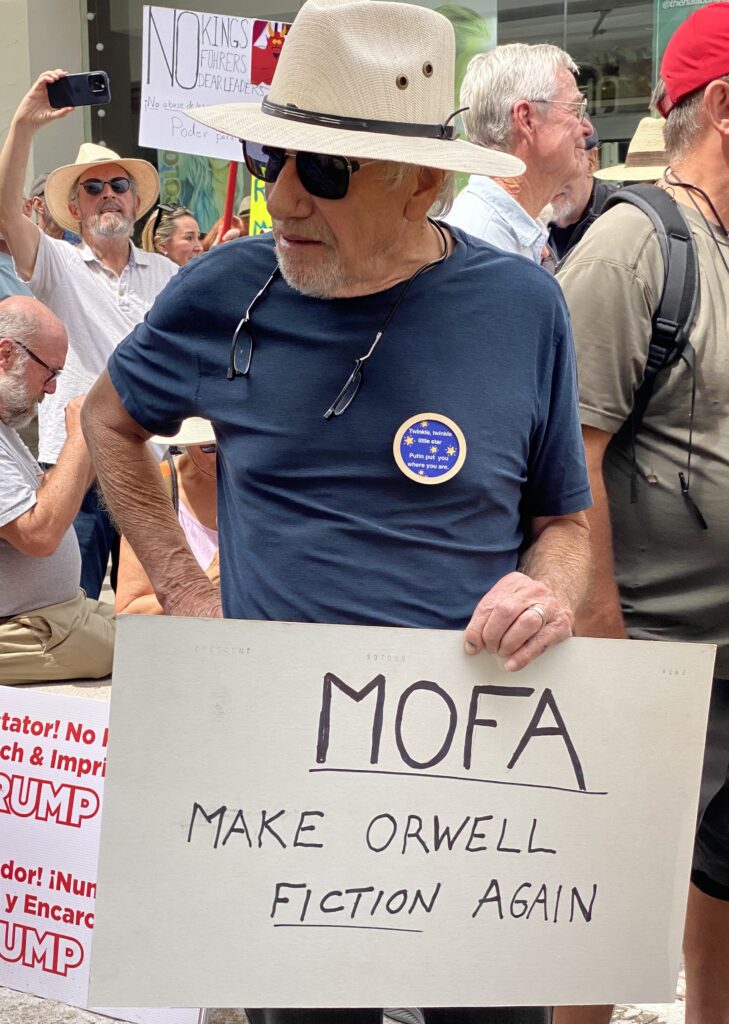

This impressively large gathering of mostly older American expats was peaceful and passionate. There was a sense of solidarity and purpose in the crowd, a friendly We’re-all-in-this-together comaraderie, which left me feeling hopeful that together we millions of passionate people can make a positive difference.

Here are more of my photos of our SMA event – some of the participants, speakers, and signs – to give you a taste of being here with us. If you were able to take part in a similar rally elsewhere in the world, please tell us about it in the Comments below and share your experience. Gracias!

(The sign this speaker is holding reads “El Maligno” [the evil one])

And there was music and singing too. As I was leaving I heard people singing “We shall overcome.” Yes, I thought: Some day.