The other night before falling asleep I had a thought – no, more like a nagging question – that tempted me to turn the light back on and inquire of my friend Professor Google. But I resisted the temptation, figuring if it were important enough I’d remember it in the morning. Which I did.

This was the burning question: “What,” I asked Prof. Google, “is the name of the Japanese art form of repairing broken pottery with gold?” Perhaps everyone knows this. But I couldn’t remember, and I needed a refresher.

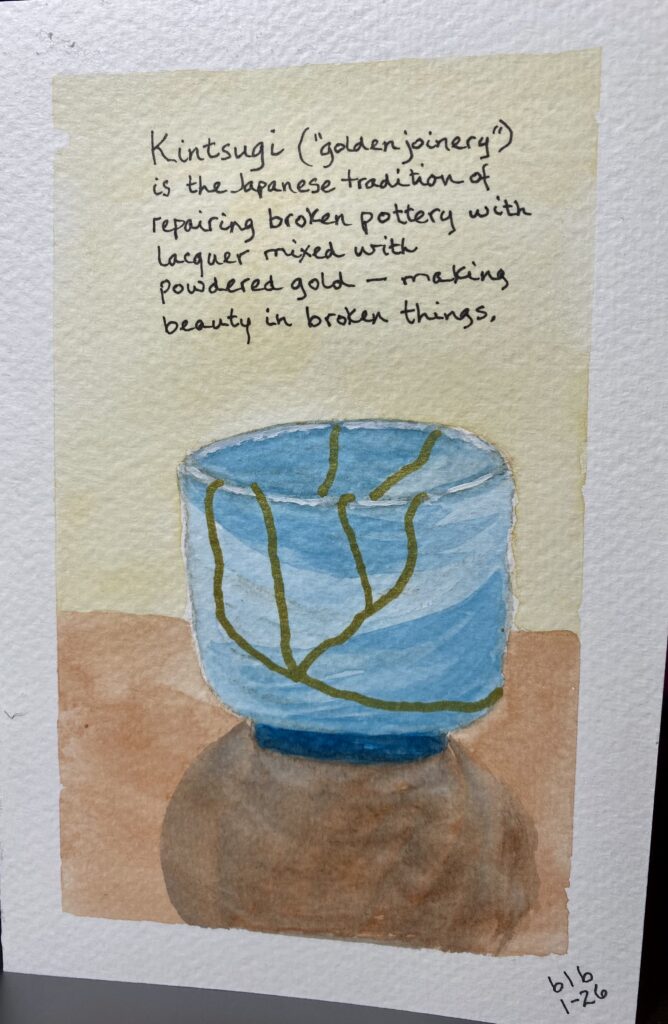

It’s Kintsugi, I learned, which in Japanese means “golden joinery.” It’s “the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with urushi lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver, or platinum…. As a philosophy, it treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise.”

As if part of me was aching for a new, New Year’s Resolution – in addition to my annual list of admonitions: Learn Spanish! and Practice watercolor painting! — I felt I’d just found it: Make a point, this coming new year, of taking worn or broken things and making art out of them. Do this in every possible sphere, on every conceivable level — concrete and abstract; physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual.

This, I know, is a tall order.

But it’s not a foreign concept to me. I remember so clearly that my mother used to make sock dolls for my sisters and me when we were little kids and she couldn’t afford to buy dolls for us at a toy store. These sock dolls were one-of-a-kind, works of art (I thought), made from, yes, our big brother’s old gym socks, with embroidered smiles and happy eyes, braided yarn hair, and dresses made from scraps of fabric she’d used to make our clothes.

“Anyone can buy things,” she’d say haughtily, flipping the script to make us feel special, “but we can make things. That’s even better!” The golden thread of her creative efforts was the sense of specialness she gave us.

Much later, in my fifties, when I taught patchwork quilting at a women’s sewing center in Segou, Mali, West Africa, as an economic development project, I found myself similarly motivated. The Malian women in my classes were poor by American standards but rich in creativity and entrepreneurial spirit. And in Segou, where much of the country’s cotton fabric was manufactured, free scraps of quilt-suitable fabric were in abundance.

Early on in my years in Segou, to my surprise, these women had asked me to teach them patchwork quilting. I’d never been a quilter, but I accepted the challenge. The first, amateurish, wall quilt I made as a demo for them is still very much in my life, more than twenty-five years later, hanging in my spare room here in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico, as a reminder of that experience:

As I wrote in my Mali memoir, HOW TO MAKE AN AFRICAN QUILT, “I worked on this new wall quilt every night in my study, while listening to French language tapes. The tiny, precise quilting stitches taught me patience, as life in Africa in general teaches patience.

“Hand quilting, I soon discovered, is far more than mere sewing. It’s a story, a statement, a commitment, a legacy. Making a quilt is actively committing to life, one small, breath-like stitch at a time.”

More recently, when I finally accepted the fact that my beloved, favorite, ten-year-old, worn-out jeans had really, really had it, and I had to, sadly, part with them, I salvaged the back pockets and made a phone pouch of them. A souvenir of the jeans that had traveled so far with me:

These are simple, homely, hand-sewn examples, I know. But the idea, like a pebble thrown far into a pond, can radiate outward. So much in our current, crazy world seems irredeemably broken (Democracy? Decency?…), which has led me – and perhaps you, too — to a sense of broken-heartedness.

But maybe, just maybe, with some creative effort, we can find ways to take the broken, torn, or worn pieces and (metaphorically, at least) glue or sew them back together into something unexpectedly beautiful and new.

So this is my resolution for 2026: repair, repurpose, reuse, revive, renew. Will you join me?

Yes, I join you ! Cheered by the indigenous tales that 2025 was the year of the snake, all bitterness, evil, destructive and 2026 is the year of the horse – strong and kind, free and leaving the past behind us! Happy and healthy New Year dear Bonnie! Xoxoxo

Oh, I didn’t know this, dear Carol. OK, then, let’s all jump on the 2026 horse and confidently gallop ahead!

Wonderful Bonnie. Coincidentally, I was talking about kintsugi last night when a friend showed me how she’d mended a bowl that appeared to be a work of art. As you suggest, it’s not just fixing things — things repaired with love take on a new soulfulness.

Yes, Kim! Soulfulness is the perfect word. Gracias!

Thank you Bonnie. What a joyful approach to this new year. So many things in our life can be repurposed….and, I think, possibly come out better than the original. Definitely joining you. Lee

Thank you, Lee, for joining in. We need all the human kintsugis we can get. 🙂

May this inspired and purposeful idea continue to blossom into all things mundane and magnificent. Our world already has too much stuff, both materially and emotionally. The intentional practice of renewing, reusing, remaking, serves the planet and those who live on it, more than we can know. Thank you!

Gracias, dear Lena, for your eloquent words! May we all work on becoming pretty little gold-laced kintsugi pots in 2026. 🙂

Oh, la Bonnie! Kintsugi sounds like a wonderful practice. I remember the quilt from your home in Taos. The phone pocket is adorable. Que bonito. Feliz 2026.

Gracias, Querida Te. Yes, this old wall quilt goes with me wherever I go! Feliz ano nuevo to you and Gary too. — Abrazos fuertes, BB xx

Oh, Bonnie, you did it again: expressed so well the beautiful art of “repairing something, Kintsugi, making it even more beautiful. When Gary and I studied the art of Japanese tea, many years ago, we learned this term and applied it to a broken porcelain tea bowl. I wish I had it now but will paint a picture of it to bring you joy in the New Year. As usual, I am inspired by your words!

The world certainly is broken; let’s hope 2026 will be the year of “beautiful repair.”

Thank you, Sher. Yes, I share your hope! Vamos a ver…

So enjoyed reading your latest Blog. I really liked your

back pocket purse creation and references to Japan.

I was in Japan in the early 60’s and will discuss with you in two weeks. Gary D.

Thanks, Gary! Yes, see you back in SMA soon. Safe travels.

All my life I have repurposed, I suppose a legacy from parents who went through the depression and the fact that I was a quasi hippie in the 70s. I feel like it’s in my DNA. I have a pile of things on my sewing table to repurpose. I hope to see you, In san miguel at sketching shortly.

Thanks for sharing your experience, Heather. I hope to get back to Sketchers soon! See you there, I hope.

Repairing what ‘s broken with gold or silver to make them. glow is such a wonderful tradition. We ahve much to repair in our world to make it whole again and glowing. gracias for your sage wordsLets jump on the horse that is coming! abrazos fuertes.

Thank you, dear Judith, for grasping the underlying message of this post. Yes, it’s the world that needs fixing, and I believe it will require all of our creative efforts and energy to even begin to repair it.

Sage advice, as always, Bonnie. I am not one to toss “broken” things and I agree with Moms advice that “anyone can BUY things!” After living together for 25 years, I still surprise my partner and love hearing him say “where has THAT been hiding” when a long thick slab of glass shelving or a roll of rare silk ribbon suddenly appears. I love your resolution and we should all join forces with hope that our broken world will find a way to fill its gaps with precious silver and gold. Happy New Year indeed, we need it now more than ever. xoxo

Dearest One-and-Only Michael-my-Archangel — THANK YOU for your kind words and your belief, too, that it’s our broken world that we all must try our best to creatively repair. Let’s hope we can achieve this feat in 2026! — LU, BB xx

Dear Bon,

I never hear of kintsugi, but what a beautiful idea it is: To repair something in a way that renders it more valuable than it was when unbroken. I fully support your idea of reusing and repurposing things, though I wish I were more handy when it comes to fixing things. I often save broken things in the hopes of someday repairing them, but it doesn’t often lead to doing so. I do think making some beautiful out of the jeans you love is brilliant. That kind of creativity is what makes you a true artist!

Love,

Paul

Thank you, Paul dear. I credit my mother Lee for teaching me this kind of practical creativity! — xx